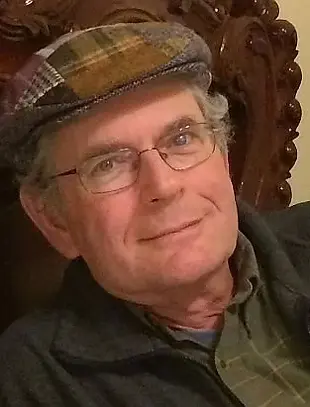

Dave Kwinter

Dave Kwinter is a Canadian-born artist based in the San Francisco Bay Area. A retired attorney with two degrees in psychology, Dave’s path has been as diverse as his art—he has practiced law, served in the Canadian military, fought forest fires, worked underground as a miner, delivered mail, and even trained goldfish for a memory study. After years of painting with acrylics and creating digital art, he discovered his true passion in assemblage, transforming found objects from thrift stores, flea markets, and sidewalks into surreal, playful, and thought-provoking sculptures. Drawing inspiration from artists like Max Ernst, H.C. Westermann, and Daniel Lind-Ramos, Dave’s work explores balance, symmetry, and disruption, often invoking the layered complexity of coats of arms or pinball machines. His art has been exhibited widely across the United States and featured in publications including American Artwork, Artistonish Magazine, and Artist Closeup Magazine.

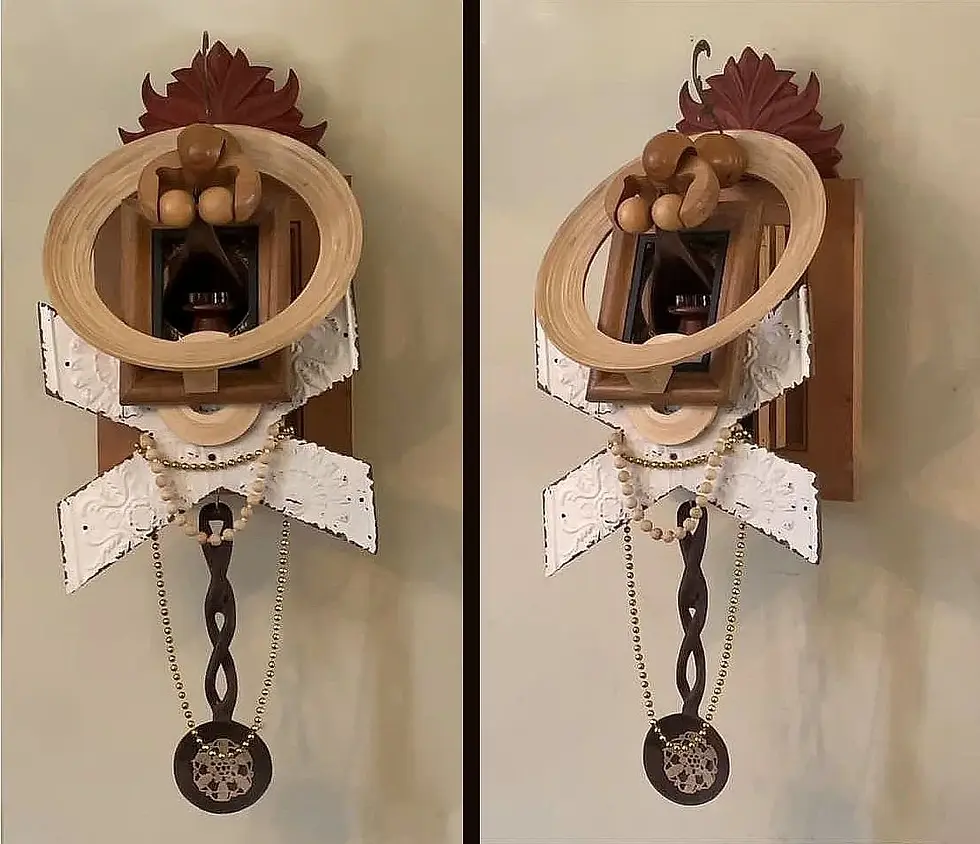

24" x 15" x 16" 2025

29"x 12" x 11" 2024

24" x 15" x 16" 2025

Dave Kwinter — The Joy of Discovery

For Dave Kwinter, art has always been an act of curiosity — an ongoing dialogue between imagination, persistence, and play. Born and raised in Toronto, Canada, and now based in the San Francisco Bay Area, Dave’s creative path has taken many turns: from painting and digital art to the playful, layered world of assemblage sculpture. “Since my teenage years, I have wanted to make art,” he reflects. “Originally I was interested in painting… later I experimented with collage and computer art programs. Seven years ago, I started doing what I’m doing now — assemblage sculpture.” That evolution came with its share of trials. As a teenager, Dave’s first attempts at oil painting ended in frustration and self-doubt. “I felt so bad about the two paintings I managed to finish that I destroyed them and abandoned painting for about five years,” he recalls. His rediscovery of painting came unexpectedly, prompted by a beginner’s acrylic set he found in a hardware store. “Painting was again painful,” he admits, “but I was able to finish some pieces which were at least moderately satisfying to me. How did I do it? I believe it was by sticking to the task despite the pain.”

That stubborn persistence — the willingness to keep going despite imperfection — has become a cornerstone of Dave’s artistic philosophy. It’s a lesson that has served him throughout his creative life, from painting to sculpture, and one that has culminated in some proud moments, such as winning first prize for one of his assemblages in a recent juried exhibition.

Dave’s process today is rooted in spontaneity and discovery. “Very early, I discovered I have much more fun when I don’t plan my artworks,” he says. “In painting, computer art, and sculpture, I like to act first, then reflect on what I have done. If I like what I did, great! If not, I modify it.” His assemblages often begin with two or three found objects — fragments from thrift stores, flea markets, or even sidewalks — that he combines intuitively, letting form and balance emerge naturally. The result is whimsical, surreal, and full of texture and humor — art that invites viewers to find meaning in the unexpected. Of course, creative freedom comes with its own setbacks. One memorable lesson arrived in the form of a kitchen catastrophe. “I was working on a sculpture on my kitchen countertop because every flat surface in my studio was covered,” he laughs. “But there wasn’t enough room, so it crashed to the floor, breaking into pieces. That event taught me to clean up and get organized.” The accident, though frustrating, sparked a transformation: “I am much more efficient now, and in a better mood since many of the items that used to lie in a heap are now sorted and stored.” Other setbacks were more emotional, such as his first rejection from a painting competition. “It was quite a disappointment,” he recalls, “but I’ve since learned that tastes vary — what one person loves, another might not.”

|  |

|---|---|

|  |

|  |

|

The experience taught him a valuable truth about art and acceptance: that the worth of a piece is not determined by external validation, but by the artist’s own satisfaction. Dave’s creative evolution also reflects a deep curiosity about process and play. He has explored realism, abstraction, and cartoon-like imagery, eventually realizing that enjoyment mattered more than technical perfection. “Realism took too much patience,” he laughs. “I had much more fun with abstraction.” His transition to assemblage brought new joy: “Working in three dimensions is much more fun than being confined to two.” Through it all, Dave has gathered hard-won wisdom that he shares generously. “Artists should try different approaches, techniques, and media,” he advises. “Try something new — it may suit you better than whatever you’ve been doing.” For him, the key is resilience. “Beginning artists give up too easily,” he observes. “If you’re unhappy with your art, ask yourself what you don’t like and what would make it better. Think about your artwork as a problem you are capable of solving — and stop expecting art making to be easy.” Unlike many artists, Dave has never felt compelled to tailor his work to the art market. “I’ve never concerned myself with adapting to audience expectations,” he says. “I’ve tried only to produce work that satisfied me.” This freedom — the luxury of creating without commercial pressure — allows him to stay true to his vision, finding joy in experimentation rather than conformity.

Inspiration comes from many places: the writings of art coach Eric Maisel, collections of artist quotations, and the works of creators he admires. Compliments, sales, and awards provide encouragement, but they’re not what drives him. Instead, it’s the thrill of discovery — the moment when disparate objects suddenly coalesce into something surprising, balanced, and alive.

To artists facing self-doubt, Dave offers warm reassurance: “Welcome to the club. Uncertainty is part of art making.” He recommends Art and Fear by David Bayles and Ted Orland — a book that explores exactly that truth. When asked how he defines success, Dave quotes sociologist Charles Horton Cooley: “An artist cannot fail; it is a success to be one.” Yet, ever the realist, he adds, “If an artist does not like his or her own art, to me, that artist is not a success. The most important criterion of success to me has always been whether I like what I did. If I like my art, that’s good enough for me.”

For Dave, art is much like humor — personal, instinctive, and sometimes misunderstood. “A work of art is like a joke,” he muses. “You either get it or you don’t. If I think it’s hilarious, even if nobody else does, I still enjoy it.” In the end, Dave Kwinter’s art is a joyful act of experimentation — a reminder that creativity thrives not on perfection, but on curiosity, persistence, and the willingness to play.